“Mountain goats. Beartooth Plateau, Wyoming," writes Jay Anderson in sharing these three photos with us. "Part of the greater Yellowstone ecosystem.” These amazingly sure-footed climbers and leapers (able to soar up to 12 feet in a single bound) are not actually goats; they're part of a family that includes gazelles and antelopes. They're able to maneuver on steep slopes in part because their cloven hooves have inner gripping pads and sharp, curved, anti-slipping dewclaws and can be spread apart for traction. The age of a mountain goat can be determined by counting the growth rings on their horns, which they don't shed. Many thanks to Jay for his photos. Have you ever seen or photographed a mountain goat?

The Unseen Gray Tree Frog

“I accidentally put my hand on this gray tree frog while hiking over lichen-covered granite boulders at Borestone Mountain Audubon Sanctuary in Guilford, Maine," writes Jill Osgood in sharing her photo with us. "The cold slimy frog under my hand made me scream, but the frog seemed unfazed. Truly amazing camouflage!”

Photo of gray tree frog by Jill Osgood

In addition to having those lichen-like blotches to hide them, Eastern gray tree frogs can change color to match their surroundings; their scientific name is, appropriately enough, Hyla versicolor. Thanks, Jill. Anyone else encountered a tree frog or other animal so well camouflaged that you've nearly missed it?

A Primate Cousin

We've been receiving more and more nature photos and sightings from people around the world lately. Mike Boydstun shared with us this arresting portrait of a long-tailed (or crab-eating) macaque that he took at the Prang Sam Yot temple in Thailand, where these highly intelligent and adaptable Old World monkeys live in large numbers and have become a tourist attraction.

Photo taken and shared with us by Mike Boydstun, who says, "This smart creature startled the heck out of me when it jumped on my back while I was shooting its cousin. Apparently they are more like us than we sometimes remember. The three local families are known to have skirmishes and battles from time to time."

With 23 species spread from Japan to Gibraltar (even small populations in Florida and South Carolina), macaques are the most widespread primates other than humans. They live in complex and fascinating social hierarchies. Unfortunately for them, they are so closely related to us (93% the same DNA) and so easy to breed and keep in captivity that several of their species—including this long-tailed variety and rhesus macaques, better known as rhesus monkeys—have long been used for human medical and psychological research. The term "rhesus factor" or "Rh factor" (positive or negative) used in describing human blood types comes from research on rhesus macaques. Rhesus macaques were central to Jonas Salk's development of the polio vaccine. They also have served as astronauts; rhesus macaques were sent into space by both the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

All animal species deserve our deep respect, but macaques are among those that merit special gratitude for their involuntary sacrifices on behalf of us humans. Many thanks to Mike for capturing in his portrait a sense of how similar to us these fellow primates are. (If you're interested in learning more about macaques, one book to consider is "Macachiavellian Intelligence: How Rhesus Macaques and Humans Have Conquered the World," by Dario Maestripieri.) —Craig Neff and Pamelia Markwood

How the Historic Supermoon Looked from All 50 States

We were thrilled and honored when—at our invitation—people from all 50 states, the District of Columbia and eight countries sent us their photos of the historic November 2016 Supermoon, the brightest, largest full Moon since 1948. Around the world, we all watched the Moon together that weekend. Click on the video to see an assortment of the great photos that were shared with us.

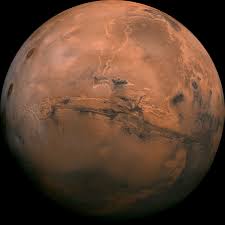

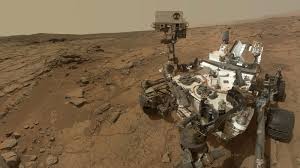

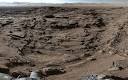

Maine on Mars! And a Visit to NASA's Jet Propulsion Lab

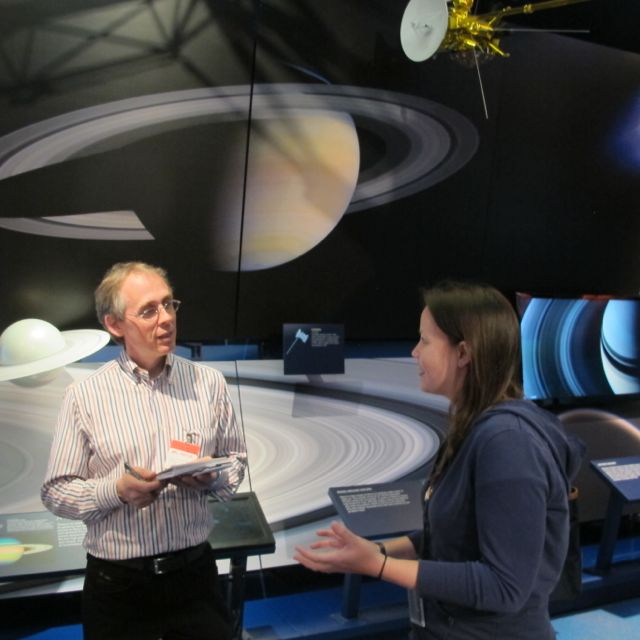

Exciting news for anyone who loves Maine: A small square of land on the surface of Mars—about 555 acres of the half-Earth-size planet—has officially been named Bar Harbor by our friend Katie Stack Morgan (below), a wonderful and brilliant young research scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, California, who works on the ongoing Curiosity rover mission.

Katie used a Mars globe at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory to show me areas the rover was and was not exploring.

The Curiosity rover has been exploring a number of Mars surface landmarks that Katie—a regular visitor to Maine's Acadia National Park with her family—has endowed with Bar Harbor-area names, such as Cadillac Mountain. This story from the local newspaper, the Mount Desert Islander, nicely sums up how Katie, as a member of the Mars project's science team, got the opportunity to name a portion of Mars (while sticking to naming guidelines set by the International Astronomical Union) and what's been happening with Curiosity's exploration of "Bar Harbor:" http://www.mdislander.com/maine-news/mars-newest-bar-harbor-world

Three summers ago we met Katie at The Naturalist's Notebook in Seal Harbor, Maine, where she was exploring our interactive science and nature installations and shopping for fun items such as our blank "Mars Passport" notebooks (she bought one and joked that she was going to use it to write down her hours working on the rover project). A few months later in Pasadena she gave Pamelia and me an amazing behind-the-scenes tour of the Jet Propulsion Lab, or JPL. It's a remarkable facility that includes not just genius scientists but also everything from a working duplicate of the rover (so that JPL technicians can troubleshoot with a real rover if the one on Mars encounters problems) to developmental labs where future spacecraft components are designed and built to a "Mars Yard," which replicates the rocky Martian surface and can be used as a testing ground for rovers. Here are some of the photos we took on our unforgettable day at the JPL:

If you haven't seen the movie The Martian, check it out—it offers an inspiring, if fictionalized, look at the remarkable JPL scientists in action (and happens to be one of our favorite films). Also try to catch National Geographic's new six-part miniseries on Mars, which is debuting in November. It's fiction as well—it follows the story of a manned voyage to Mars in the year 2033—but I'm guessing it will be as scientifically accurate as the filmmakers could make it. Here's a link to the trailer for the miniseries:

http://channel.nationalgeographic.com/mars/videos/mars-trailer-1/

Congratulations to Katie on literally putting Bar Harbor and Maine on the map (of Mars). For those of you who have been to Acadia National Park and Bar Harbor, now seems like an especially good time to start following NASA's exciting exploration of the red planet. —Craig Neff and Pamelia Markwood

Good News for the Antarctic

A year ago at this time we were on our way to Antarctica on a Russian oceanographic vessel. Among the things we learned en route to and on the planet's coldest, wildest continent (besides the fact that we could ride out 50-foot waves—see slide show) was that the surrounding Southern Ocean waters are massively important both in sustaining the world's ocean food chain (through the abundance of tiny, bottom-of-the-food-chain krill, among other things) and in driving the deep-water currents that are crucial in shaping Earth's climate and transporting nutrients (as extra-cold, extra-salty water sinks to the bottom and moves across the ocean floor). All of which makes this a week to celebrate.

That's because 24 countries and the European Union have agreed to protect an ecologically vital part of the Southern Ocean known as the Ross Sea by creating the world's largest protected marine area—600,000 square miles, and the first such area to be established in international waters rather than the waters of one country. The deal is far from perfect (it expires in 35 years, primarily because of objections from Russia, which is trying to protect its fishing industry), but the hope among conservationists is that this will be the first in a series of Antarctic ocean sanctuaries—protected areas that might help stop us humans from screwing up yet another unique, life-sustaining portion of our fragile planet.