We were thrilled and honored when—at our invitation—people from all 50 states, the District of Columbia and eight countries sent us their photos of the historic November 2016 Supermoon, the brightest, largest full Moon since 1948. Around the world, we all watched the Moon together that weekend. Click on the video to see an assortment of the great photos that were shared with us.

Maine on Mars! And a Visit to NASA's Jet Propulsion Lab

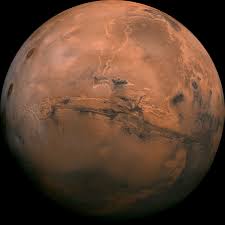

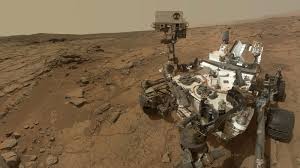

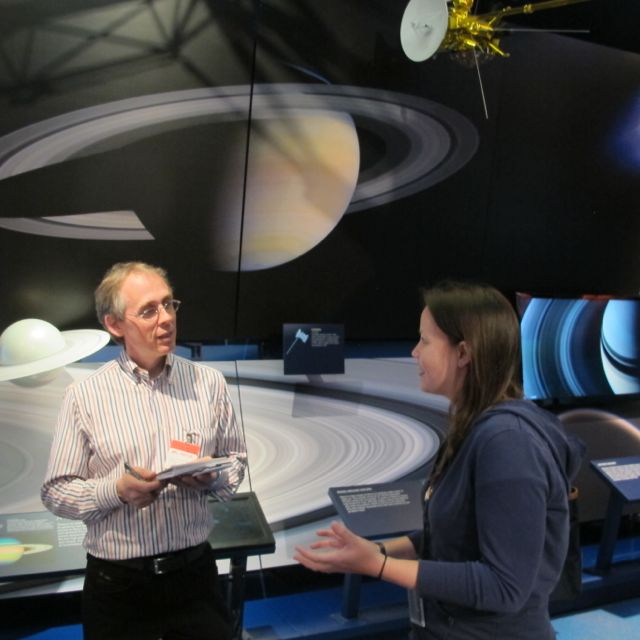

Exciting news for anyone who loves Maine: A small square of land on the surface of Mars—about 555 acres of the half-Earth-size planet—has officially been named Bar Harbor by our friend Katie Stack Morgan (below), a wonderful and brilliant young research scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, California, who works on the ongoing Curiosity rover mission.

Katie used a Mars globe at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory to show me areas the rover was and was not exploring.

The Curiosity rover has been exploring a number of Mars surface landmarks that Katie—a regular visitor to Maine's Acadia National Park with her family—has endowed with Bar Harbor-area names, such as Cadillac Mountain. This story from the local newspaper, the Mount Desert Islander, nicely sums up how Katie, as a member of the Mars project's science team, got the opportunity to name a portion of Mars (while sticking to naming guidelines set by the International Astronomical Union) and what's been happening with Curiosity's exploration of "Bar Harbor:" http://www.mdislander.com/maine-news/mars-newest-bar-harbor-world

Three summers ago we met Katie at The Naturalist's Notebook in Seal Harbor, Maine, where she was exploring our interactive science and nature installations and shopping for fun items such as our blank "Mars Passport" notebooks (she bought one and joked that she was going to use it to write down her hours working on the rover project). A few months later in Pasadena she gave Pamelia and me an amazing behind-the-scenes tour of the Jet Propulsion Lab, or JPL. It's a remarkable facility that includes not just genius scientists but also everything from a working duplicate of the rover (so that JPL technicians can troubleshoot with a real rover if the one on Mars encounters problems) to developmental labs where future spacecraft components are designed and built to a "Mars Yard," which replicates the rocky Martian surface and can be used as a testing ground for rovers. Here are some of the photos we took on our unforgettable day at the JPL:

If you haven't seen the movie The Martian, check it out—it offers an inspiring, if fictionalized, look at the remarkable JPL scientists in action (and happens to be one of our favorite films). Also try to catch National Geographic's new six-part miniseries on Mars, which is debuting in November. It's fiction as well—it follows the story of a manned voyage to Mars in the year 2033—but I'm guessing it will be as scientifically accurate as the filmmakers could make it. Here's a link to the trailer for the miniseries:

http://channel.nationalgeographic.com/mars/videos/mars-trailer-1/

Congratulations to Katie on literally putting Bar Harbor and Maine on the map (of Mars). For those of you who have been to Acadia National Park and Bar Harbor, now seems like an especially good time to start following NASA's exciting exploration of the red planet. —Craig Neff and Pamelia Markwood

Good News for the Antarctic

A year ago at this time we were on our way to Antarctica on a Russian oceanographic vessel. Among the things we learned en route to and on the planet's coldest, wildest continent (besides the fact that we could ride out 50-foot waves—see slide show) was that the surrounding Southern Ocean waters are massively important both in sustaining the world's ocean food chain (through the abundance of tiny, bottom-of-the-food-chain krill, among other things) and in driving the deep-water currents that are crucial in shaping Earth's climate and transporting nutrients (as extra-cold, extra-salty water sinks to the bottom and moves across the ocean floor). All of which makes this a week to celebrate.

That's because 24 countries and the European Union have agreed to protect an ecologically vital part of the Southern Ocean known as the Ross Sea by creating the world's largest protected marine area—600,000 square miles, and the first such area to be established in international waters rather than the waters of one country. The deal is far from perfect (it expires in 35 years, primarily because of objections from Russia, which is trying to protect its fishing industry), but the hope among conservationists is that this will be the first in a series of Antarctic ocean sanctuaries—protected areas that might help stop us humans from screwing up yet another unique, life-sustaining portion of our fragile planet.

Supermoon As Seen Across America

During this month's Hunters Moon Supermoon (which looked 16% larger than a typical full Moon and 30% brighter because the Moon was 16,500 miles closer to Earth than it is on average), hundreds of people shared with us on our Facebook page their photos of the event. These were taken with everything from cellphones to long lenses to telescopes. It was thrilling to see so many people excited by looking up at the evening sky.

We're hoping even more people will become Moon-watchers on November 13 and 14, when they'll be able to see the largest, brightest, closest full Moon since 1948. The November Supermoon will be known as a Beaver Moon, borrowing a Native American term for a November full Moon. We won't see another full Moon this close and large until the year 2014...so don't miss it. And enjoy this video we put together with some of the October Supermoon photos. —Craig Neff and Pamelia Markwood

Rare Sight: Two California Condors

Bob Maloy shared with us this photo after he was lucky enough to see two extremely rare and critically endangered California condors from a bridge over the Colorado River in Arizona.

How rare is the California condor? This type of vulture—North America's largest bird, with a wingspan of up to 10 feet—dwindled to just 22 known individuals by the 1980s because of hunting, habitat loss, lead poisoning (from the bullets in the carcasses on which these scavengers feed), DDT poisoning and collisions with power lines.

Those 22 survivors were captured and put in a breeding program, one limited by the fact that the birds can't reproduce before age six and generally lay just one egg every one or two years in the wild. (In the breeding program, that egg is removed, prompting the female to lay a second and even third one; the chicks from the removed eggs are raised using condor hand-puppets so that the chicks don't imprint on humans, as shown in this video clip: http://www.arkive.org/…/gymnogyps-california…/video-15b.html).

Offspring from this painstaking and heroic breeding program have been released over the last 25 years to try to rebuild the wild population, which now stands at almost 250—a fragile number, especially given that all of them descend from just 14 of the 22 condor survivors of the 1980s. Despite a California ban on lead bullets, condors continue to die from lead poisoning, possibly from bullets in carcasses elsewhere in their range, which includes Arizona, Utah and Mexico.

It's interesting to note that in the Pleistocene era (which began about 2.5 million years ago) the California condors' range was vastly larger, extending from what's now Canada to Mexico, across the American South and up the East Coast to New York. That range shrank dramatically 10,000 years ago after the extinction of mastodons, giant ground sloths, saber-tooth cats, camels and other big ground mammals. Our thanks go out to scientists and other conservationists for keeping the California condor from joining that list of extinct animals.

Many thanks as well to Bob for sharing his rare photo with us. He says that the two condors he saw in Arizona bore the wing-tag numbers 54 and H9—biologists have named and tagged all the released condors to keep track of them—and that he also saw an immature one in the area. What an experience.

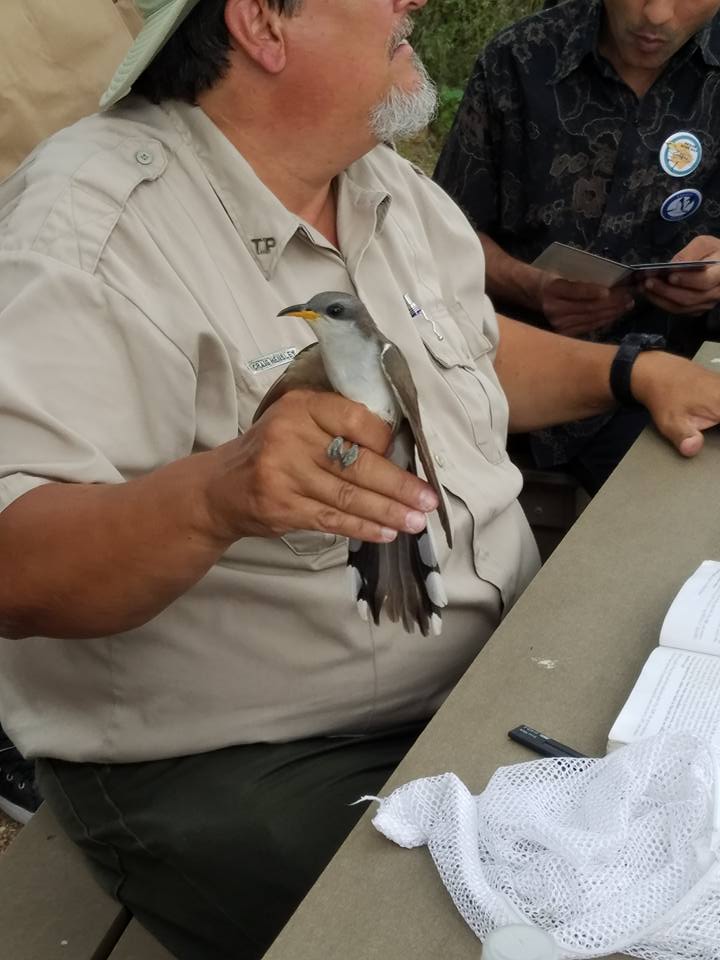

The Yellow-Billed Cuckoo

If you've ever wondered if cuckoos are real birds or just cuckoo-clock accessories, here's proof that they're real. Melissa Patton took this photo in Alabama of a yellow-billed cuckoo, one of many beautiful and fascinating species in the cuckoo family.

Yellow-billed cuckoo photo by Melissa Patton

Cuckoos of one sort or other are found on every continent except Antarctica. Their name comes from the sound of the call of the common cuckoo (formerly known as the European cuckoo). That bird's constant, seemingly mindless repetition of its call led people to use "cuckoo" to mean "crazy." Click here to listen to that common-cuckoo call: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O5N7KHSlBRU

Meanwhile, female common cuckoos' habit of laying eggs in other birds' nests led to the coining of the word "cuckold," describing a husband whose wife has cheated on him. Yellow-billed cuckoos do not share this habit, which is known as brood parasitism. (Below are more yellow-billed cuckoo photos—and a beautiful painting—shared with The Naturalist's Notebook by our followers on Facebook.)

Like most cuckoos, the yellow-billed is long-tailed and prefers feeding on on insects. Indeed, it's one of the few birds willing to eat hairy caterpillars. A hungry yellow-billed can down 100 in one session. That appetite can help control infestations of tree-defoliating tent caterpillars—one more reason to be cuckoo about cuckoos.